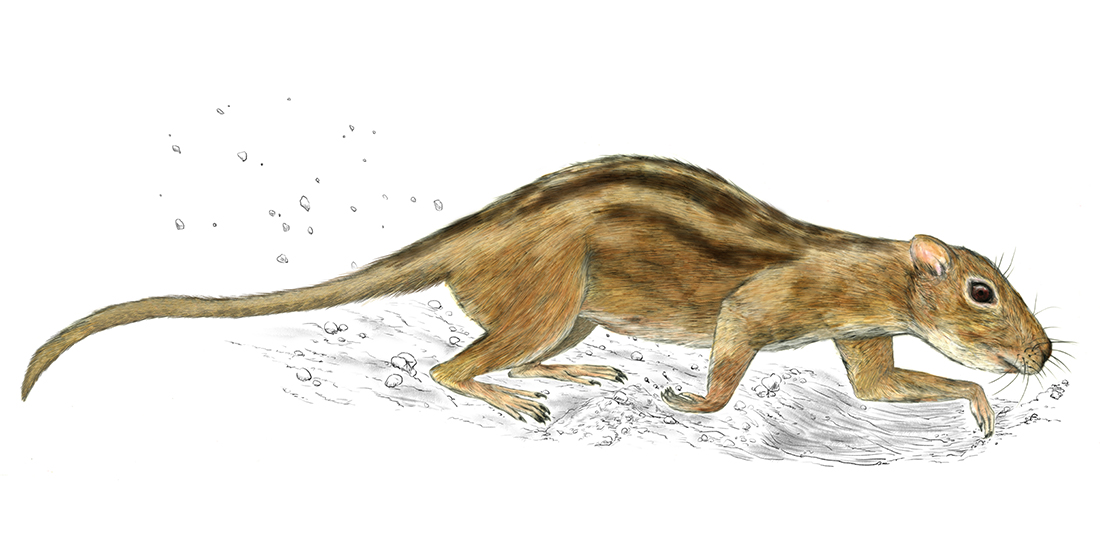

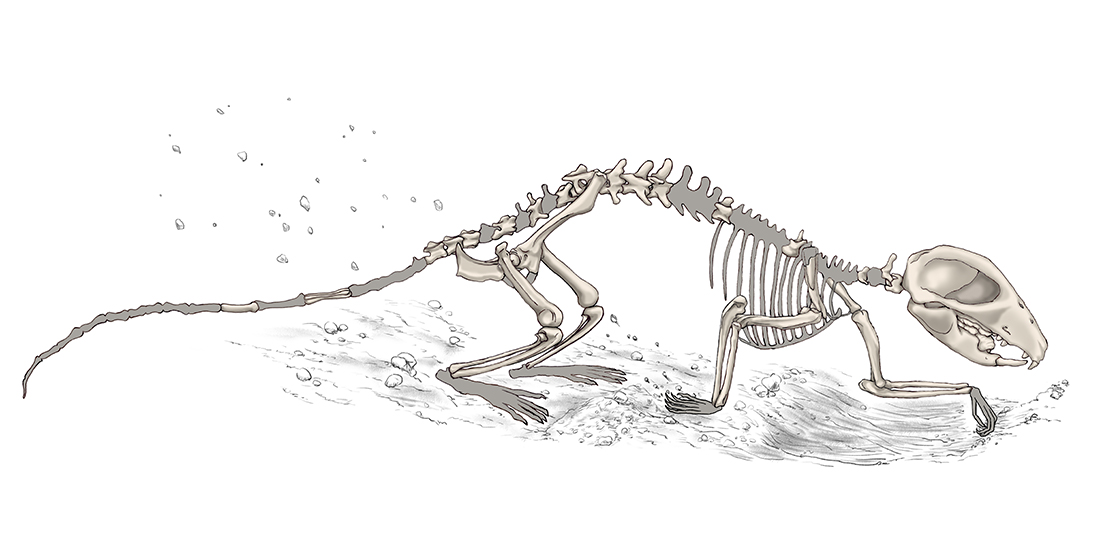

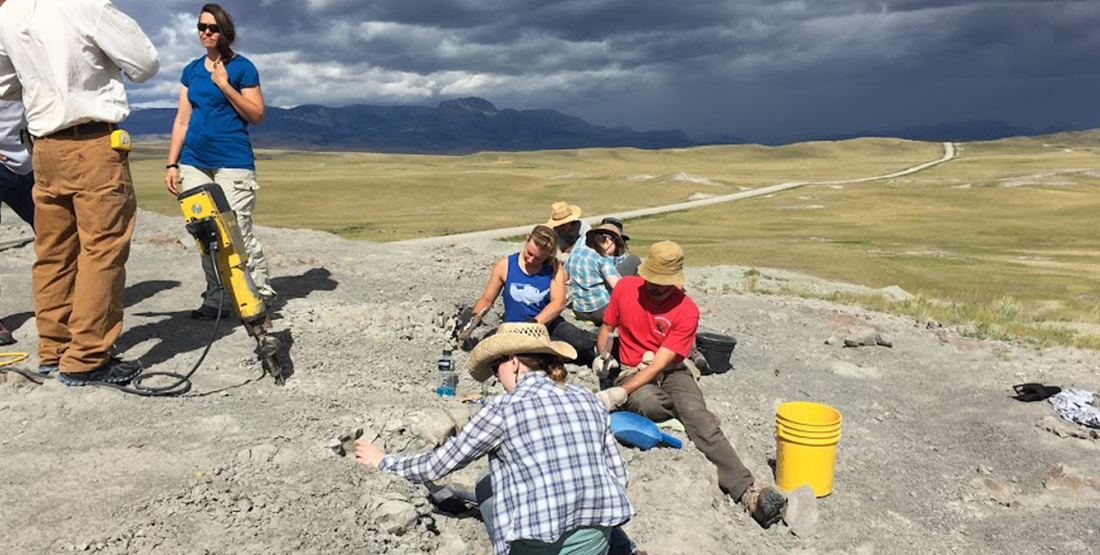

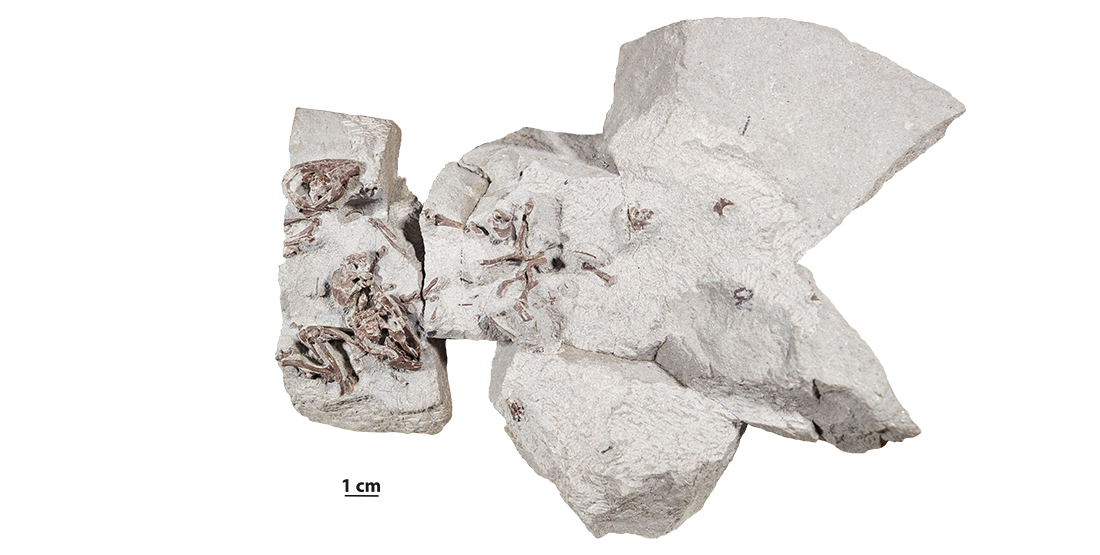

The evidence lies in the fossil record of a new genus of multituberculate—a small, rodent-like mammal that lived during the Late Cretaceous of the dinosaur era—called Filikomys primaevus (translates to “youthful, friendly mouse”). The fossils, which are the most complete mammal fossils ever found from the Mesozoic in North America, indicate that F. primaevus engaged in multi-generational, group-nesting and burrowing behavior, and possibly lived in colonies. University of Washington Biology and Burke Museum Graduate Student Luke Weaver, UW Professor of Biology and Burke Museum Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology Gregory Wilson Mantilla, and co-authors analyzed several fossils, extracted from a well-known dinosaur nesting site called Egg Mountain in western Montana, that are about 75.5 million years old.

Fossil skulls and skeletons of at least 22 individuals of F. primaevus were discovered at Egg Mountain, typically clustered together in groups of two to five, with at least 13 individuals being found within a 30 m2 area in the same rock layer. Based on how well preserved the fossils are, the type of rock they’re preserved in, and F. primaevus’ powerful shoulders and elbows that are similar to today’s living burrowing animals, Weaver, Wilson Mantilla, and co-authors hypothesize these animals lived in burrows and were nesting together. Furthermore, the animals found were a mixture of multiple mature adults and young adults, suggesting these were truly social groups as opposed to just parents raising their young.

“It was crazy finishing up this paper right as the stay-at-home orders were going into effect—here we all are trying our best to socially distance and isolate, and I’m writing about how mammals were socially interacting way back when dinosaurs were still roaming the Earth!” Weaver said. “It is really powerful, I think, to see just how deeply rooted social interactions are in mammals. Because humans are such social animals, we tend to think that sociality is somehow unique to us, or at least to our close evolutionary relatives, but now we can see that social behavior goes way further back in the mammalian family tree. Multituberculates are one of the most ancient mammal groups, and they’ve been extinct for 35 million years, yet in the Late Cretaceous they were apparently interacting in groups similar to what you would see in modern-day ground squirrels.”

It is really powerful to see just how deeply rooted social interactions are in mammals.

— Luke Weaver, Burke Museum and UW Biology Graduate Student

Previously, scientists thought social behavior in mammals first emerged after the mass extinction that killed off the dinosaurs, and mostly in the group of mammals humans belong to, called Placentalia (mammals that have the fetus carried in the mother’s uterus until a late stage of development). But these fossils show mammals were socializing during the Age of Dinosaurs, and in an entirely different and more ancient group of mammals—the multituberculates.

“These fossils are game changers,” Wilson Mantilla said. “As paleontologists working to reconstruct the biology of mammals from this time period, we’re usually stuck staring at individual teeth and maybe a jaw that rolled down a river, but here we have multiple, near complete skulls and skeletons preserved in the exact place where the animals lived. We can now credibly look at how mammals really interacted with dinosaurs and other animals that lived at this time.”

For high resolution images and interviews, contact burkepr@uw.edu.

Study Information:

Lucas N. Weaver, David J. Varricchio, Eric J. Sargis, Meng Chen, William J. Freimuth, Gregory P. Wilson Mantilla. November 2, 2020. Early Mammalian Social Behaviour revealed by Multituberculates from a Dinosaur Nesting Site.