Previously, mammals in the Age of Dinosaurs were thought to be a relatively small part of their ecosystems and considered to be small-bodied, nocturnal, ground-dwelling insectivores. According to this long-standing theory, it wasn’t until the K-Pg mass extinction event (approximately 66 million years ago) that wiped out all non-avian dinosaurs that mammals were then able to flourish and diversify. An astounding number of fossil discoveries over the past 30 years has challenged this theory, but most studies looked only at individual species and none has quantified community-scale patterns of the rise of mammals in the Mesozoic.

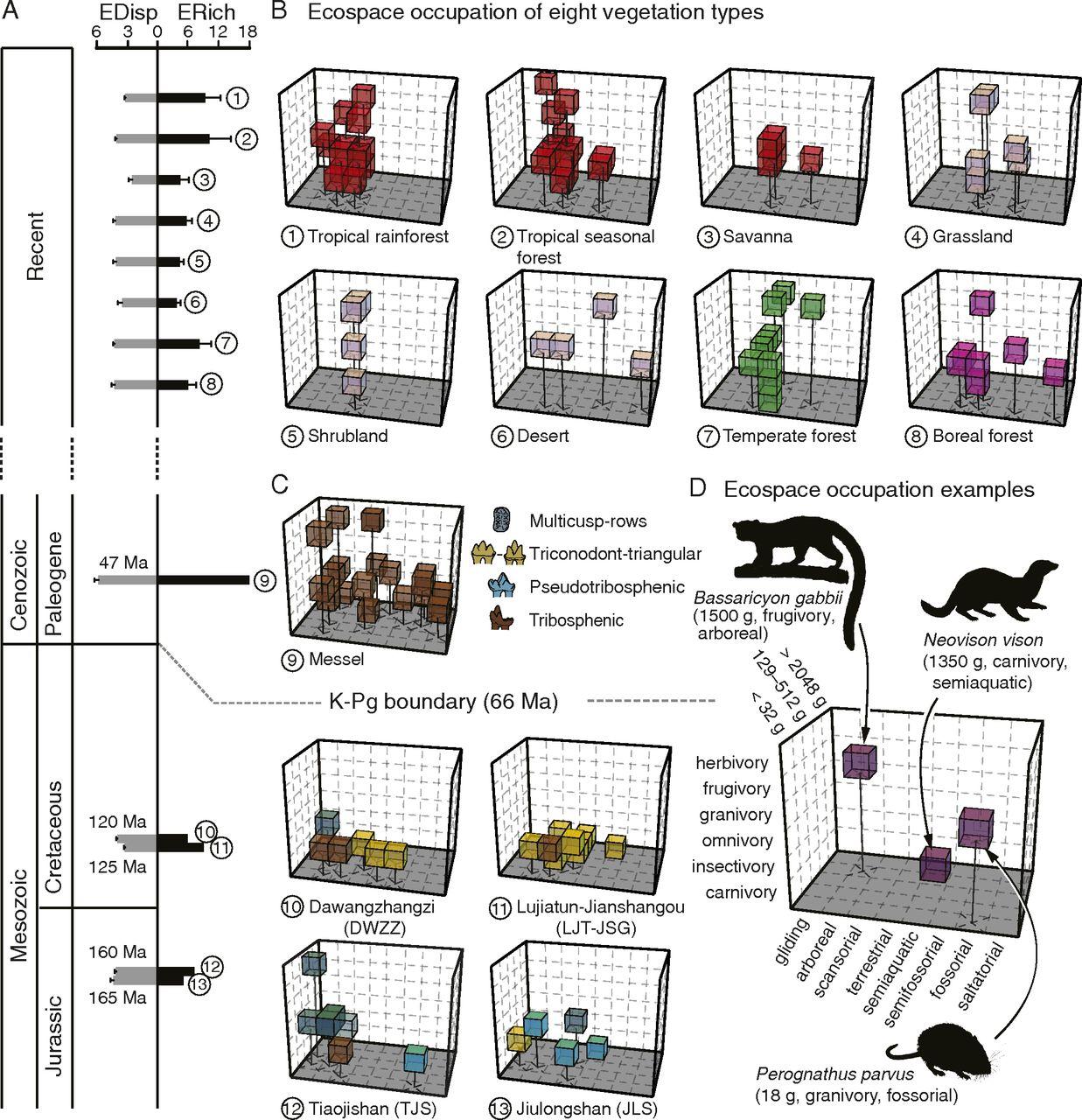

Co-authors Nanjing University School of Earth Sciences and Engineering postdoc fellow and University of Washington Biology alumnus, Dr. Meng Chen, University of Washington Biology Professor and Burke Museum Curator of Paleobotany, Dr. Caroline Strömberg, and UW Biology Associate Professor and Burke Museum Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology, Dr. Gregory Wilson, created a Rubik’s Cube-like structure identifying 240 “eco-cells” representing possible ecological roles of mammals in a given ecospace. These 240 eco-cells cover a broad range of body size, dietary preferences, and ways of moving (locomotion) of small-bodied mammals. When a given mammal filled a certain type of role or eco-cell, it filled a spot in the ‘Rubik’s Cube'. This method provides the first comprehensive analysis of evolutionary and ecological changes of fossil mammal communities before and after K-Pg mass extinction.

“We cannot directly observe the ecology of extinct species, but body size, dietary preferences and locomotion are three aspects of their ecology that can be relatively easily inferred from well-preserved fossils,” Chen said. “By constructing the ecospace using these three ecological aspects, we can visually identify the spots filled by species and calculate the distance among them. This allows us to compare the ecological structure of extinct and extant communities even though they don’t share any of the same species.”

The team analyzed living mammals to infer how fossil mammals filled roles in their ecosystems. They examined 98 small-bodied mammal communities from diverse biomes around the world, an approach that has not been attempted at this scale. They then used this modern-day reference dataset to analyze five exceptionally preserved mammal paleocommunities―two Jurassic and two Cretaceous from northeastern China, and one Eocene community from Germany. Usually Mesozoic mammal fossils are incomplete and consist of fragmentary bones or teeth. Using these remarkably preserved fossils enabled the team to infer ecology of these extinct mammal species, and look at changes in mammal community structure during the last 165 million years.

The team found that, in current communities of present-day mammals, ecological richness is primarily driven by vegetation type, with more small mammals filling eco-cells (41 percent) compared to the paleocommunities (16 percent). The five mammal paleocommunities were also ecologically distinct from modern communities and pointed to important changes through evolutionary time. Locomotor diversification occurred first during the Mesozoic, possibly due to the diversity of microhabitats, such as trees, soils, lakes, and other substrates to occupy in local environments. It wasn’t until the Eocene that mammals grew larger and expanded their diets from mostly carnivory, insectivory and omnivory to include more species with diets dominated by plants, including fruit. The team determined that the rise of flowering plants, new types of teeth, and the extinction of dinosaurs likely drove these changes.

Before the rise of flowering plants, mammals likely relied on conifers and other seed plants for habitat, and their leaves and possibly seeds for food. By the Eocene, flowering plants were both diverse and dominant across forest ecosystems. Flowering plants provide more readily available nutrients through their fast-growing leaves, fleshy fruits, seeds, and tubers. When becoming dominant in forests, they fundamentally changed terrestrial ecosystems by allowing for new modes of life for a diversity of mammals and other forest-dwelling animals, such as birds.

“Flowering plants really revolutionized terrestrial ecosystems,” Strömberg said. “They have a broader range of growth forms than all other plant groups―from giant trees to tiny annual herbs―and can produce nutrient-rich tissues at a faster rate than other plants. So when they started dominating ecosystems, they allowed for a wider variety of life modes and also for much higher ‘packing’ of species with similar ecological roles, especially in tropical forests.”

Tribosphenic molars (complex multi-functional cheek teeth) became prevalent in mammals in the Late Cretaceous. Mutations and natural selection drastically changed the shapes of these molars, allowing them to do new things like grinding. In turn, this allowed small mammals with these types of teeth to eat new kinds of foods and diversify their diets.

Lastly, the K-Pg mass extinction event that wiped out all dinosaurs except birds 66 million years ago provided an evolutionary and ecological opportunity for mammals. Small body size is a way to avoid being eaten by dinosaurs and other large vertebrates. The mass extinction event not only removed the main predators of mammals, but also removed small dinosaurs that competed with mammals for resources. This ecological release allowed mammals to grow into larger sizes and fill the roles the dinosaurs once had.

“The old theory that early mammals were held in check by dinosaurs has some truth to it,” Wilson said. “But our study also shows that the rise of modern mammal communities was multifaceted and depended on dental evolution and the rise of flowering plants.”

---

Study Information: Assembly of modern mammal community structure driven by Late Cretaceous dental evolution, rise of flowering plants, and dinosaur demise. Meng Chen, Caroline A. E. Strömberg, and Gregory P. Wilson. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Published on April 29, 2019.https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1820863116