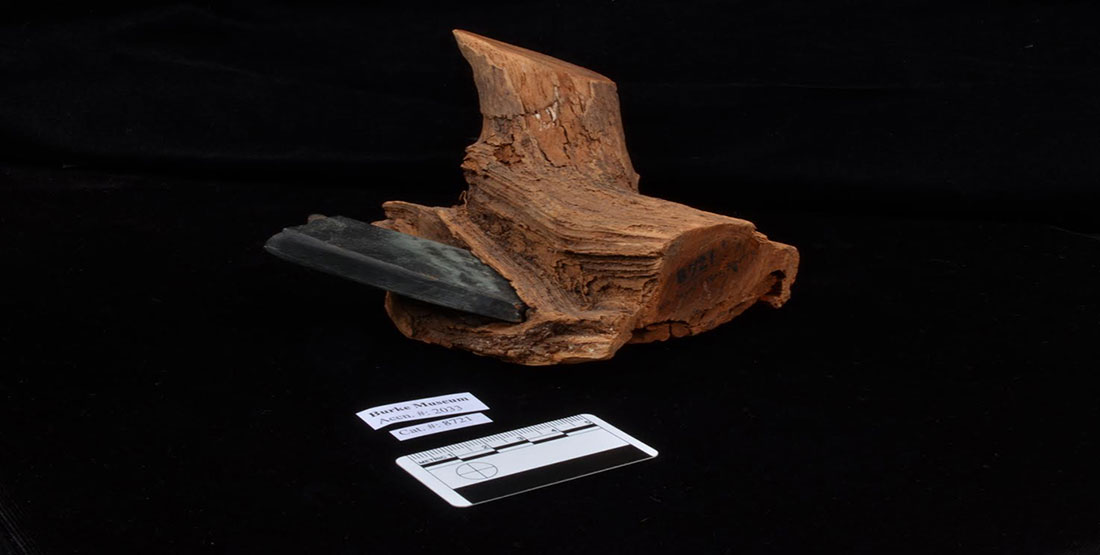

The object, a stone woodcarving adze broken and embedded in a piece of cedar, is unlike most items in our archaeological collections. The adze seems alive to me, stopped midchop by a recalcitrant cedar branch, abandoned by its user. Making adzes out of stone is a labor of love; Coast Salish people transformed large jadeite boulders, probably deposited on Puget Sound beaches by glaciers, into blades using other tools and sand as an abrasive. Whoever made and owned this adze would not have abandoned it easily. This artifact tells us about the beauty of a well-made tool, the frustrations of woodworking and the nature of western red cedar.

Lately, I’ve taken a fresh look at our collections in preparation for the Burke’s new building and exhibits. In the process, I’ve come to learn more about the adze and how its story relates to Seattle’s.

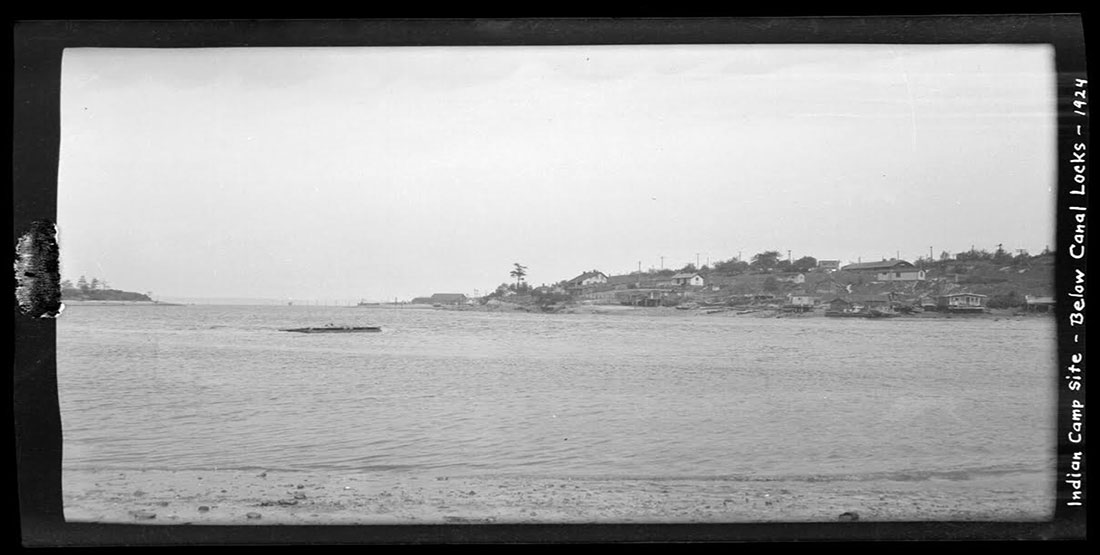

Museum records give hints about the object’s rediscovery in 1923 near the Ballard Locks on the banks of Salmon Bay, listing the donor as an engineer named Christenson. More clues come from handwritten notes in the Burke archives titled Report of field service man, A. G. Colley: Dec. 1923, On result of 18 days wk. at site of ancient camp at near Chisholm Bay and US Gov. Locks. A. G. Colley excavated sites around the Puget Sound region and beyond from the 1920s through the 1940s, and Christenson’s rediscovery of the adze likely led Colley to dig up several more artifacts from near the adze find-site, which are also now in the Burke’s collections. Colley speculates that erosion from the wakes of ships and efforts to widen the channel between the locks and Puget Sound exposed the remains of the Coast Salish settlement where the adze was found.

As detailed in Coll Thrush’s 2007 book Native Seattle, prior to the 1850s, the village of Shilshole (Lushootseed for “tucked away inside”) was situated a bit further east of where the adze was rediscovered and had two to three longhouses. Beginning in the mid-19th century, throughout the Puget Sound region, non-Native settlers forcibly (often violently) moved Coast Salish people out of traditional villages and denied them access to traditional territories.

In 1913, the building of the Ballard Locks gave US government Indian agents a reason to forcibly evict two of the last Shilshole people living on the shores of Salmon Bay, Hwelchteed and Cheethluleetsa, an older married couple. Cheethluleetsa died at home around the time of the eviction, and Hwelchteed moved to the Port Madison Reservation, repeating a story of displacement that has taken place in the region over and over.

The Ballard Locks dramatically altered the natural flow of water, fish and people in and around Seattle. In 1923, just 10 years after Cheethluleetsa and Hwelchteed were evicted, the adze that I’ve admired was rediscovered in the eroding banks of the busy Ship Canal. Seattle had been utterly changed in that decade — Salmon Bay had been transformed from one of the last Coast Salish settlements in the city to a ship highway. Although Coast Salish people continued to live in the city, they could no longer occupy and protect ancestral places like Shilshole. Instead, those sites became places of academic interest—“camps” where “field service men” like A. G. Colley could dig with impunity and engineers like Christenson could happen upon Native artifacts exposed by the work of his peers.

Today, my discipline of archaeology is finally coming to terms with this history of excluding indigenous people. Archaeological excavations of Coast Salish sites in the Puget Sound area are now monitored (and often managed) by tribal archaeological staff. I would argue that Seattle still has a ways to go in recognizing its indigenous history and the continuing presence of indigenous people in the city, which is all the more apparent as we witness another era of profound and rapid urban transformation.

For me, this cultural artifact is now more than a mini tableau of adze-in-wood, stuck in the past. Though the artifact is ancient, it now signifies for me an ongoing story, one in which Coast Salish ancestors may have paused in their work to witness engineers construct locks and ship canals, waiting for the right moment to reassert their claims to land and history.

---

Learn more about the Burke Museum cultural collections.