A $2.5 million National Science Foundation grant will daylight thousands of specimens from their museum shelves by CT scanning 20,000 vertebrates and making these data-rich, 3D images available online to researchers, educators, students and the public.

The project oVert, short for openVertebrate, complements other NSF-sponsored museum digitization efforts, such as iDigBio, by adding a crucial component that has been difficult to capture—the internal anatomy of specimens.

With virtual access to specimens, researchers could peel away the skin of a passenger pigeon to glimpse its circulatory system, a class of third graders could determine a copperhead’s last meal, undergraduate students could 3D print and compare skulls across a range of frog species and a veterinarian could plan a surgery on a giraffe in a zoo.

“In a time when museums and schools are losing natural history collections and giving up due to costs, we are recognizing the information held in these specimens is only getting more valuable,” said project co-principal investigator Luke Tornabene, assistant professor of aquatic and fishery sciences at the University of Washington (UW) and curator of fishes at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture.

“I think this project is going to help create a renaissance of the importance of natural history collections,” he said.

The UW joins 15 other institutions in this new project, led by the Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida. The grant will enable researchers over four years to transport specimens from museum collections to scanners, scan and upload images, and organize them on the public database MorphoSource for easy access.

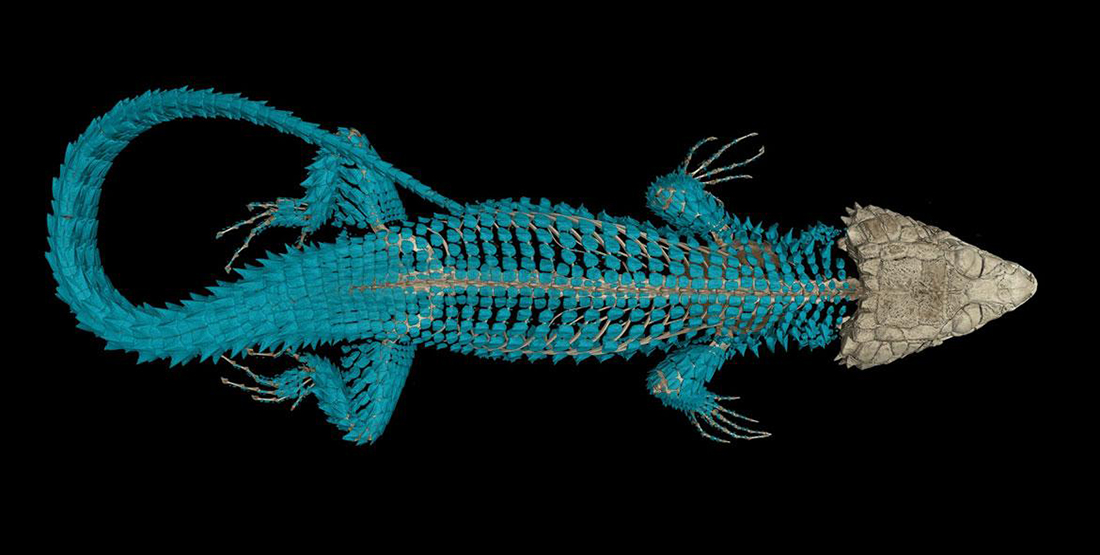

More than one quarter of the world’s vertebrate species will be scanned and digitized through this project, and researchers will aim to include specimens from more than 80 percent of existing vertebrate genera. A selection of these will also be scanned with contrast-enhancing stains to characterize soft tissues. There are almost 70,000 vertebrate species described today, and more than half of those are fishes.

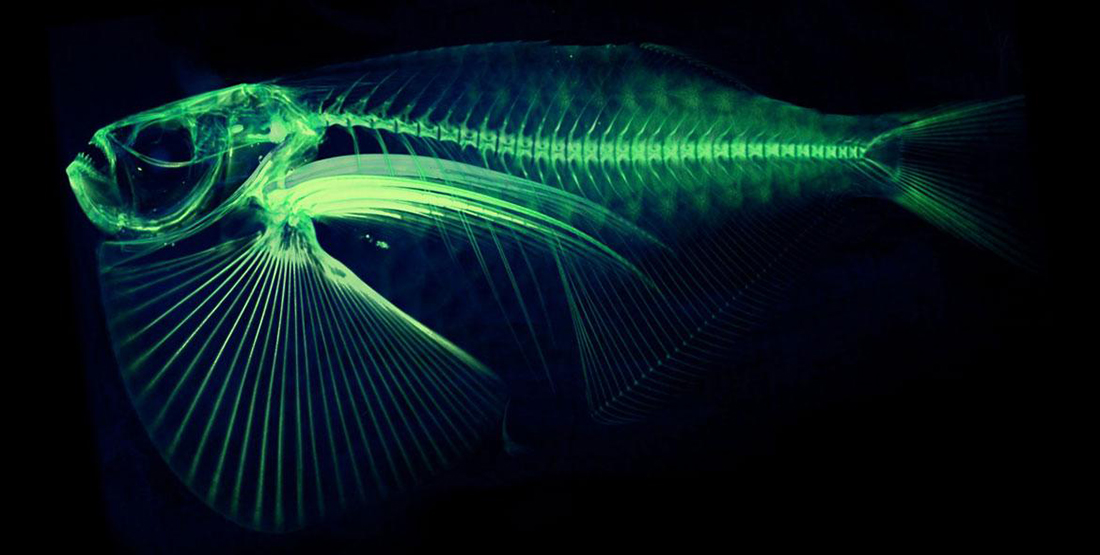

The UW has already made a dent in scanning and digitizing many of the fish species included in this project through the #ScanAllFishes effort, led by Adam Summers, a UW professor of aquatic and fishery sciences and of biology. For the past two years, Summers and colleagues have used a small CT scanner at Friday Harbor Laboratories to produce scores of fish scans from specimens gathered around the world.

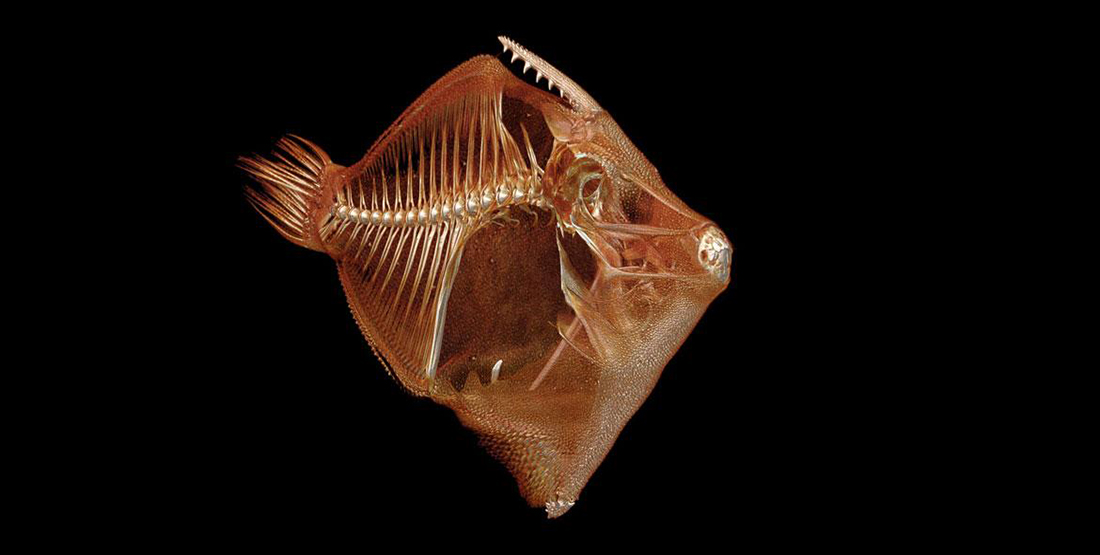

CT scanning is a non-destructive technology that bombards a specimen with X-rays from every angle, creating thousands of snapshots that a computer stitches together into a detailed 3-D visual replica that can be virtually dissected, layer by layer, to expose cross-sections and internal structures.

The scans allow scientists to view a specimen inside and out—its skeleton, muscles, internal organs, parasites, even its stomach contents—without touching a scalpel.

“Our goal is to provide data that offer a foothold into vertebrate anatomy across the Tree of Life,” said David Blackburn, oVert’s lead principal investigator and associate curator of amphibians and reptiles at the Florida Museum of Natural History. “This is a unique opportunity for museums to have a pretty big reach in terms of the audience that interacts with their collections. We believe oVert will be a transformative project for research and education related to vertebrate biology.”

In addition to the UW and University of Florida, scanning will occur at the University of Michigan, Harvard University, Texas A&M University and the Field Museum at the University of Chicago. The team’s largest scanner can image specimens as large as a garbage can, so for large mammals, scientists will focus on scanning their skulls or other key anatomical features, Tornabene said.

In contrast, micro-CT scanners like the one at Friday Harbor Labs can pick up incredible detail of small vertebrates that are difficult to study at life size, he explained. UW scientists have scanned some of the smallest fish in the world and can zoom in to the digital file to examine anatomy not visible with the naked eye. They can also 3D print specimens larger than life.

“We are going to be exploring the capabilities of understanding vertebrate anatomy at the finest scales,” Tornabene said.

The UW’s three CT scanners will focus mainly on digitizing key species in the Burke Museum’s collection of 12 million fish specimens, as well as the museum’s large bat collection. In addition to Tornabene and Summers, Katherine Maslenikov, Burke Museum fish collections manager, and Sharlene Santana, curator of mammals at the Burke Museum and assistant professor of biology, will lead the effort at the UW.

###

This release was adapted from a Florida Museum of Natural History release.